-40%

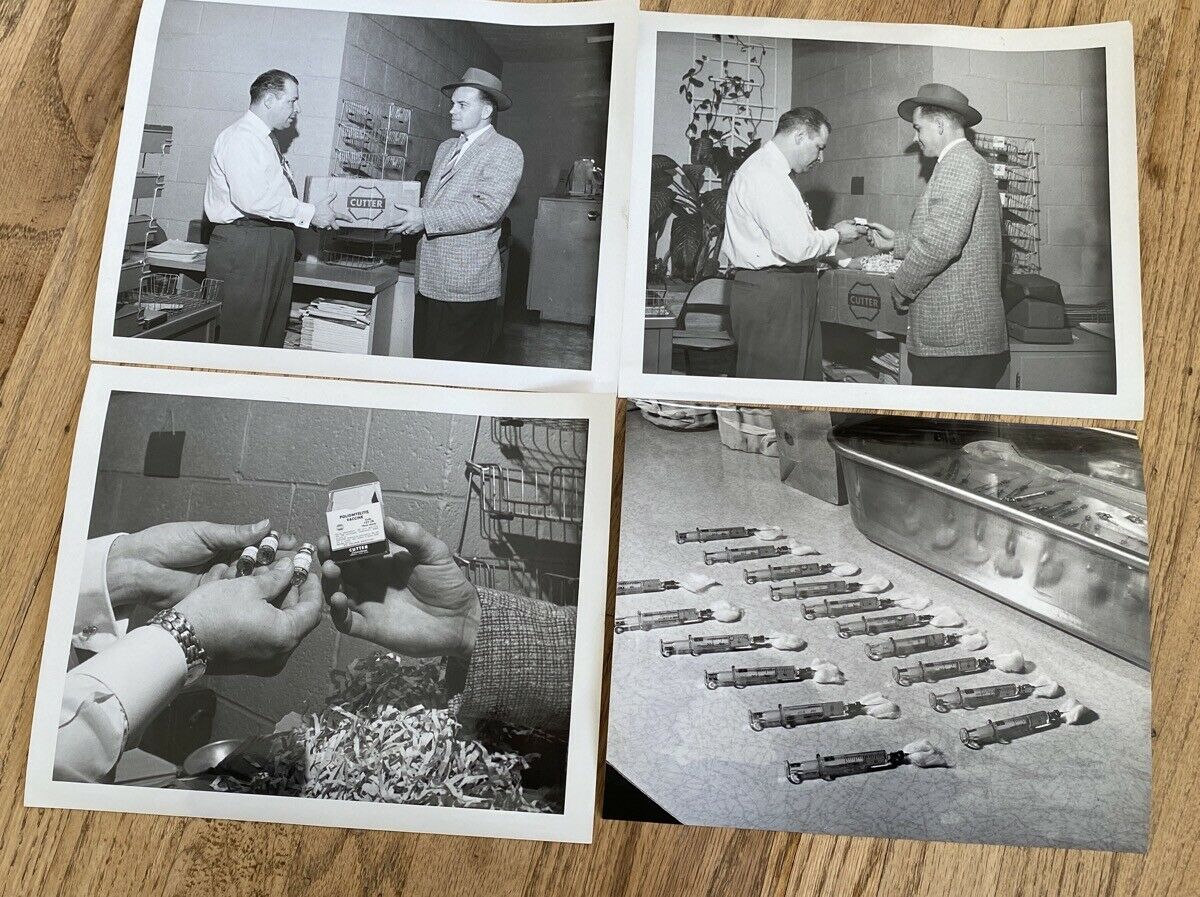

Berkeley Cutter Laboratories Historical Photographic Record Polio vaccine

$ 1320

- Description

- Size Guide

Description

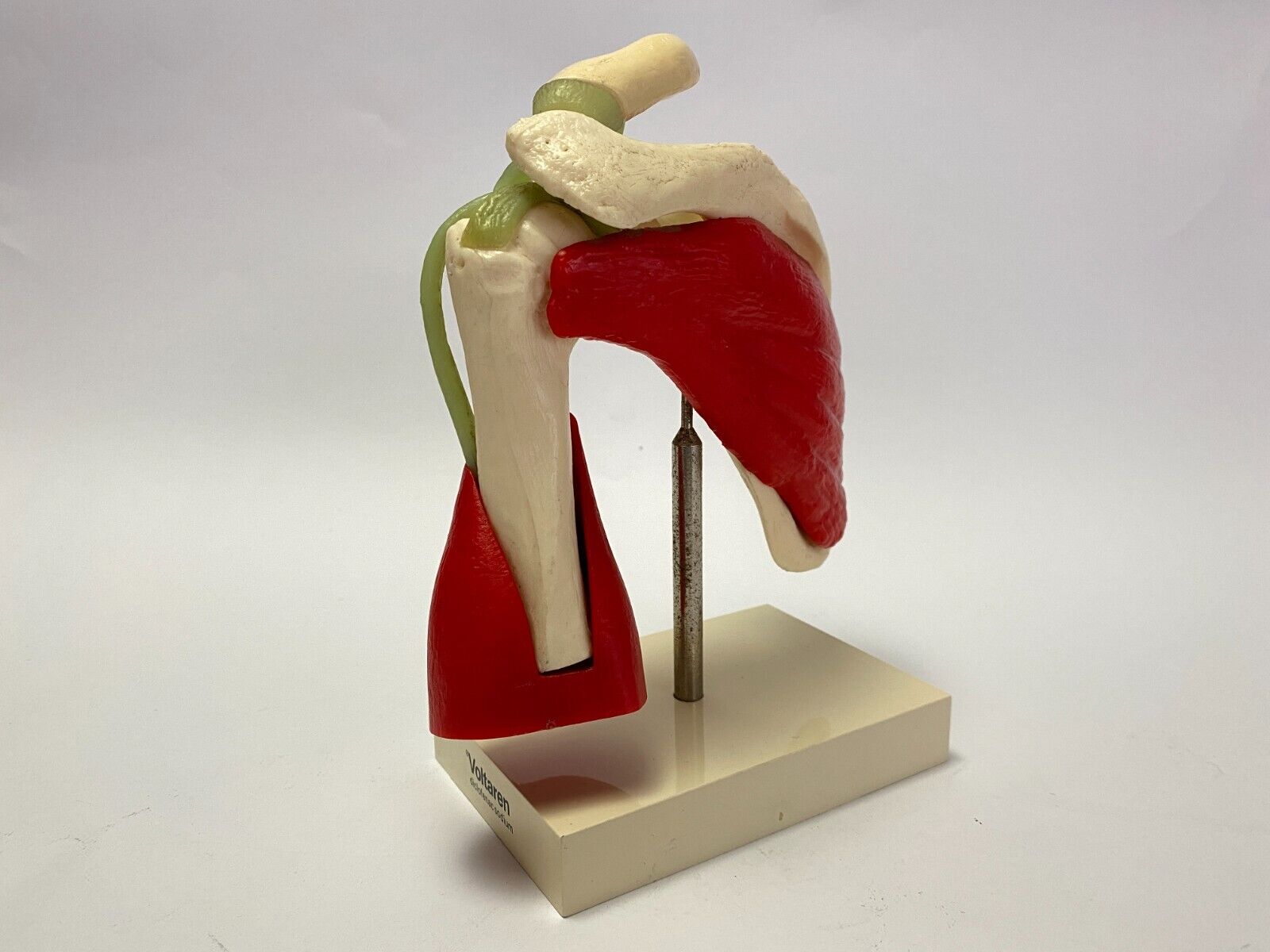

Historical photographic record: Berkeley Cutter Labs Polio vaccine disaster.This auction is for a collection of thirty 1954-55 Cutter Laboratories Berkeley California crisp focused black and white 8x10 photographs. These images include testing efficiency of polio vaccine, tissue cell extraction process, rhesus monkeys, filtering polio vaccine, polio packaging photos, polio preparation of animal tissue, preparing media, visually checking vaccine before packaging, polio filtering flask with media, planting polio virus in flask, tissue culture safety testing, checking media, washing flasks, technicians observing virus growth, incubating polio flask. Many have taped typed information on the back. Some yellowing from the tape on backs of photos.

Many of the photos are by Elmer Moss Photography, 15 California St., San Francisco. Moss Film Productions, produced films for the Navy, as well as footage for KRON- TV and medical film for Cutter Laboratories in Berkeley, Ca.

Note this information- On April 12, 1955, following the announcement of the success of the polio vaccine trial, Cutter Laboratories became one of several companies that was recommended to be given a license by the United States government to produce Salk's polio vaccine. In anticipation of the demand for vaccine, the companies had already produced stocks of the vaccine and these were issued once the licenses were signed. In what became known as the Cutter incident, some lots of the Cutter vaccine—despite passing required safety tests—contained live polio virus in what was supposed to be an inactivated-virus vaccine. Cutter withdrew its vaccine from the market on April 27 after vaccine-associated cases were reported. The mistake produced 120,000 doses of polio vaccine that contained live polio virus. Of children who received the vaccine, 40,000 developed abortive poliomyelitis (a form of the disease that does not involve the central nervous system), 56 developed paralytic poliomyelitis—and of these, five children died from polio. The exposures led to an epidemic of polio in the families and communities of the affected children, resulting in a further 113 people paralyzed and 5 deaths. The director of the microbiology institute lost his job, as did the equivalent of the assistant secretary for health. Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare Oveta Culp Hobby stepped down. Dr William H. Sebrell, Jr, the director of the NIH, resigned. Surgeon General Scheele sent Drs. William Tripp and Karl Habel from the NIH to inspect Cutter's Berkeley facilities, question workers, and examine records. After a thorough investigation, they found nothing wrong with Cutter's production methods. A congressional hearing in June 1955 concluded that the problem was primarily the lack of scrutiny from the NIH Laboratory of Biologics Control (and its excessive trust in the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis reports). A number of civil lawsuits were filed against Cutter Laboratories in subsequent years, the first of which was Gottsdanker v. Cutter Laboratories. The jury found Cutter not negligent, but liable for breach of implied warranty, and awarded the plaintiffs monetary damages. This set a precedent for later lawsuits. All five companies that produced the Salk vaccine in 1955—Eli Lilly, Parke-Davis, Wyeth, Pitman-Moore, and Cutter—had difficulty completely inactivating the polio virus. Three companies other than Cutter were sued, but the cases settled out of court. The Cutter incident was one of the worst pharmaceutical disasters in US history, and exposed several thousand children to live polio virus on vaccination. The NIH Laboratory of Biologics Control, which had certified the Cutter polio vaccine, had received advance warnings of problems: in 1954, staff member Dr. Bernice Eddy had reported to her superiors that some inoculated monkeys had become paralyzed and provided photographs. William Sebrell, the director of NIH, rejected the report.